I woke up and looked around. I seemed to be in some sort of medical facility. It was cold, industrial, with metallic beds. I couldn’t make sense of it. I tried to think back, to piece together what had happened. Nothing. I knew it was Thanksgiving morning, but I had no idea where I was or how I’d gotten there.

An attendant walked in and I asked, ‘What’s going on? Where am I? How did I get here?’ She told me that I had checked myself into the inpatient clinic at Bayridge Lynn Hospital. I had evidently driven there during a ‘blackout’ — unconscious, but still (sort of) functioning.

As the fog in my brain began to lift, I realized that I could easily have been killed. My once-promising life would have ended suddenly at age 39. Worse, I might have killed someone else, even multiple people. I was appalled. As I lay in that hospital bed, I felt sick to my stomach. I couldn’t believe what I had done, nor how badly it might have turned out.

Sadly, but not surprisingly, no one came to the hospital to check on me. My husband and children didn’t come. My parents didn’t come. Nor did any friends — though I’m not sure I still had any left. I was at the very lowest point in my life . . . and I was alone. Why? Because I was addicted to alcohol. Though it was killing me, I simply couldn’t stop drinking.

The Industry

My name is Ann-Marie Keltner, one of Eventide’s most recent hires. I want you to know why I joined Eventide, and why I chose to share this especially painful part of my story.

Some faith-oriented mutual funds, including Eventide, choose not to invest in alcohol-related businesses. That strikes many Christian investors as legalistic, or puritanical. They quickly counter that the Bible does not prohibit drinking alcohol. Jesus drank wine. He even made wine for a marriage feast about to run dry. We agree — Scripture offers no blanket command to avoid alcohol.

Still, that’s not necessarily the most appropriate consideration when it comes to investing. In fact, evaluating whether to invest in alcohol companies provides a very useful case study for how we might think about all of our investing choices.

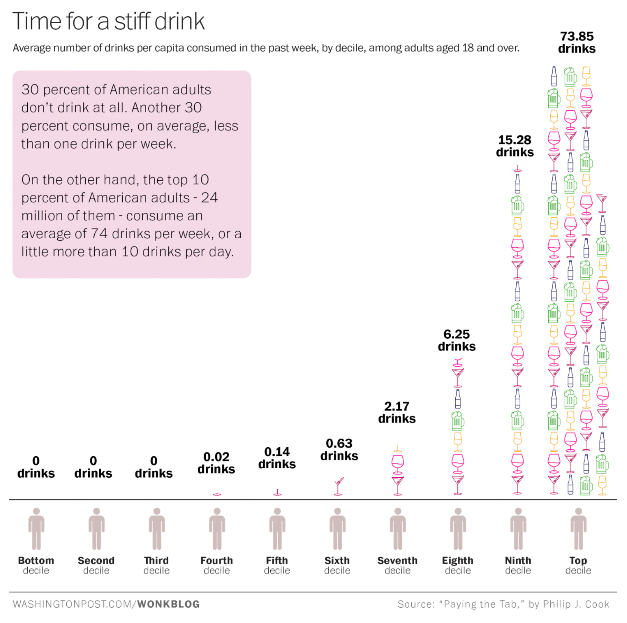

Take a look at the chart below from the Washington Post about U.S. drinking patterns:

As of 2014

As you can see, approximately one third of Americans don’t drink at all. For another third, it’s one drink or less per week. But for the top ten percent, the picture is entirely different — they average 74 drinks per week. That’s more than four-and-a-half 750 ml bottles of Jack Daniels, 18 bottles of wine, or three 24-can cases of beer. As the Post’s article notes, at this level of consumption, “you almost certainly have a drinking problem.”

This has important implications for the alcohol industry. The top ten percent of drinkers account for well over half of the alcohol consumed in any given year. In fact, a full 90 percent of alcohol sales come from just the top 20 percent of buyers.

According to Philip J. Cook, author of Paying the Tab, “One consequence is that the heaviest drinkers are of greatly disproportionate importance to the sales and profitability of the alcoholic-beverage industry.” He adds, “If the top decile somehow could be induced to curb their consumption level to that of the next lower group (the ninth decile), then total ethanol sales would fall by 60 percent.”

Is drinking alcohol wrong? Is it prohibited by Scripture? No, and no. But are the vast majority of the alcohol industry’s revenues and profits earned from people like me? Absolutely. Which means the industry is directly contributing to the addiction, misery, and premature deaths, of a great many people.

The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) says that in the U.S. app. 100,000 people die from alcohol-related causes annually, making alcohol the third-leading preventable cause of death. (The first is tobacco.) Globally, 3 million deaths in 2016 were attributable to alcohol consumption.

In fact, alcohol misuse is the very first-leading risk factor for premature death and disability among people ages 15 to 49. And 14 percent of total deaths among people ages 20 to 39 are alcohol attributable.

Furthermore, underage drinking provides a non-trivial portion of industry profits — and death and destruction in the lives of young people. The NIAAA reports that alcohol is a factor in the deaths of thousands of people younger than age 21 in the U.S. each year. It also notes that 1 in 5 college women experience sexual assault during their time in college, most of which is related to alcohol consumption.

All of which means that the alcohol industry does not earn most of its revenues and profits from people like (most of) you, i.e., people who enjoy an occasional glass of wine. Rather, the large majority of its profits — and those of its investors — are earned from the dysfunction, devastation, and death it brings to far too many lives. Lives like mine.

So let me tell you more about the devastation drinking unleashed in my own life.

Descent

I grew up in a warm, loving upper-middle-class Catholic family. No one in my family drank. But in America, it’s almost considered a rite of passage to drink heavily when you’re young. Alcohol is readily available, and popular culture portrays drinking as cool, mature, and a never-ending party. I absorbed these messages and started drinking with my friends when I was in high school. I loved how alcohol made me feel. Partying quickly became my number one priority.

Eventually I graduated from high school, from college, and then earned a master’s degree at an Ivy League university. I also became a (very-high-functioning) alcoholic — though I was still far from acknowledging that fact.

Sort of by accident, I found myself working in Manhattan on the equity derivatives trading floor of an international bank. I passed my Series 7, 63, and 24 and embraced the work hard/play hard Wall Street lifestyle. By now, I was drinking every day, starting at around 4:30 in the afternoon. I had the ‘fabulous’ life I wanted — and I was rapidly becoming more and more miserable. Really, I hated myself. I couldn’t look in the mirror. My friends and family didn’t know what was wrong with me.

Destruction

I didn’t know what was wrong with me either . . . so I drank more. This led to a further cascade of alcoholic destruction. My life now only had room for two things — work and drink. I lost any ability to relate to others, or even to do basics like clean my apartment. It was disgusting — so much so that on September 11, 2001, when two of my New Jersey colleagues were trapped in Manhattan, I couldn’t even offer them a place to stay. I simply couldn’t face having anyone see the squalor in which I was living. Of course, that added another layer to my self-loathing.

I decided to leave New York, thinking that a relocation would solve my problems. This turned out to be the first in a string of failed hopes that people and places would fix me. I built a house and met my husband, a wonderful, loyal man who doesn’t drink. I thought marriage would save me. It didn’t. I had two children. I thought being a mom would fix me. It didn’t.

When all of these failed (and I love my husband and children as much as anyone), I fell further. After my second child, I had a miscarriage. For the pain, my doctor gave me oxycodone, and for my anxiety, a benzodiazepine. I quickly became addicted to both.

I wanted to stop, but couldn’t. I went through two different rehabs. I was such a mess that my husband filed for divorce and would have gained full custody of our young children. Family and friends had all learned to stay away.

Recovery

Somehow, by the hand of God, I went to one last place called Plymouth House. It was different in two fundamental ways. First, it’s run by former alcoholics and addicts, and second, their program for recovery was the 12 Steps.

The underlying premise of the 12 Steps program is that any addict’s recovery requires surrender to a higher power. At the time, I had long since stopped believing in Jesus as anything other than a historically well-respected teacher, and my concept of God was some kind of vague, pantheistic spirit. But the recovering alcoholics at Plymouth House believed in a God with whom you have a personal relationship — a God that you give your life over to in order to stay alive.

My instinctive reaction was that this sounded superstitious and old-fashioned. I was too educated, too modern, too sophisticated. But then I looked at my ragged, broken self and my pitiful situation. And I looked at the people working at Plymouth House — they were confident, content, authentic. Who was I to say that they were wrong and I was right? Look at where my ‘sophisticated’ thinking had gotten me.

Still, I couldn’t imagine that anything would restore me to sanity. I had tried and failed so many times that I no longer believed I could be fixed. But my Plymouth House counselors said that only one thing would work — fully surrendering my life to God.

I realized I was standing on a cliff. Behind me was only death and destruction — including a heartbroken husband and children. Before me? I had no idea. With my eyes closed, I took a step into the unknown and said the Third Step Prayer of Surrender. I have said it every morning since.

I never had another drink. By God’s extraordinary grace I am now nearly ten years sober. I can’t explain what happened exactly. But after that prayer I began to see the world differently, and my place in the world differently. It wasn’t all about me anymore.

Still, there is much that has been hard. Healing from the brokenness in my life, and the brokenness I caused in other lives, has been a long, slow process. Today, though, I am hugely blessed — my marriage and family have been restored, and I find myself humble and content. I still have flaws and failings. But I know I am loved, and I am pleased with who and how God made me.

Recently I joined Eventide. I was thrilled to find a place where my Wall Street experience could be harnessed to a higher purpose — to the kind of ‘investing that makes the world rejoice.’

What Jesus did for me, he has been doing for 2000 years. Shouldn’t we make sure our investing doesn’t come at the expense of the very lives he is trying to save?